Wednesday, June 1, 2011

Comics – Creator or Character Part IX: Conclusion, part the 2nd

AND WE COME TO THE END:

Today, there are more opportunities for artists and writers working in North American comics to publish their own work while retaining ownership of the creation. Publishers like Oni Press, Top Shelf Productions, Slave Labor Graphics, and Fantagraphics are only a handful of the rising tide of publishers offering homes for original works from talented creators.

There’s more than just superheroes!

And it seems to me that when a creator is afforded the opportunity of owning his or her own works – creations that otherwise would never have been published because the “artistic voice” of every writer and every artist is so unique unto him or herself – that work will be, in accordance with other factors such as talent and intelligence, far better than a narrative slung over a corporate entity. When one is personally invested in the creation and subsequent success of a story, then one is likely to put more time and effort into it.

Alan Moore has written some beautiful Superman stories. Grant Morrison became known in America after writing Animal Man. John Byrne made his name with X-Men. Warren Ellis wrote Thor. Kevin O’Neill did some early work with Green Lantern. And these stories all have a high level of craft and quality in them, and many of them are revered by fans and professionals alike. But, I would argue, those stories are not these creators’ most compelling, or most challenging, or most emotionally satisfying works.

Respectively, From Hell, the Invisibles, Next Men, Transmetropolitan, and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, are all far more critically acclaimed than any of their superhero work. And, in my opinion, they are far, far better than the corporate comics these artists and writers have worked on. This is due to a number of factors, not the least of which is the pride one feels in the creation of something that is completely his or her own.

IT’S SUPER, MAN:

And the Big Two publishers – Marvel & DC – seem to understand, better than they ever have, the importance of the creators to the comics they publish. Certainly, it’s still not where it probably should be, but at least there have been steps taken toward a wider acknowledgement of the contribution these writers and artists bring to the stories they tell.

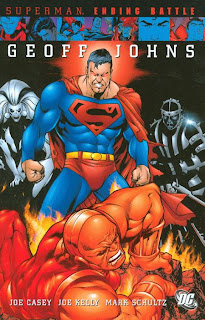

Just look at the prominence creators such as Geoff Johns now get (his name is larger than even Superman’s, and far more prominent than the other three writers, on the cover for the Ending Battle collection, in which he only wrote one-quarter of the storyline). DC is selling Geoff Johns’s name, which is a far cry from their marketing of even ten years ago. And the acclaim that artists and writers such as Johns or Ed Brubaker or George Perez receive is well-deserved. They sell books and they represent a certain artistic vision that is appealing to a lot of readers – whether that vision translates into good comics is a completely subjective and very different argument, but the impact cannot be debated.

Others, like Jim Lee with his work on Batman: Hush or the team of Brian Michael Bendis & Alex Maleev on Daredevil, are more proof that the big companies are learning what it means to have a “name” creator on a book – sales! And they seem to be doing far more than they ever have to keep these creators happy and working for them.

In the past twenty years, we’ve seen imprints such as Vertigo at DC comics or, more recently, ICON at Marvel comics, be havens where big-name creators can go to make the comics they want to make while also retaining ownership. With the likes of Vertigo and ICON, DC and Marvel get to keep big-name talent such as Grant Morrison or Warren Ellis or Ed Brubaker working for them, both in the mainstream superhero universes and these boutique publishing imprints.

It is something that DC understood far earlier than Marvel and has allowed us fans to enjoy comics such as Sandman or Criminal that we might not have been able to enjoy otherwise. And for these creators who earn such an arrangement, it’s the best of both worlds. They get to play in the big “sandbox” while also writing and drawing their own books, all under a single publishing umbrella.

THE MORE THINGS CHANGE:

Of course, this new understanding does not mean that the corporate philosophy doesn’t still reign supreme. Editorial edicts continue to be put forth, pushing creators into storylines they might not have even considered. And, for the most part, many of these incidents wreak of Marvel or DC snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

Take, for example, J. Michael Straczynski’s tenure on Amazing Spider-Man. His run with John Romita, Jr. was, in the main, well regarded. Certainly, there were people who balked at the Spider totem and nit-picked as fans are wont to do. But, up to the point JRJr left the book, it was undoubtedly a success, critically and commercially.

Then editorial started sticking their noses in until fans got “One More Day,” a story loudly derided by fans and critics, and a story that JMS wished to take his name off – it having gone so far away from his ideas that it wasn’t truly his story anymore – but Straczynski relented out of respect for Joe Quesada and Marvel comics. As a result of such editorial interference – and, ultimately, not allowing the creator, JMS, who was hired to create Spider-Man stories – much of the latter half of Straczynski’s run on the book is looked upon quite poorly.

In fact, there were two storylines from this second half of JMS’s run that made their way onto Comics Alliance’s “15 worst comics of the decade” list last year. Both “One More Day” and “Sins Past” were either editorially driven or had a heavy editorial hand involved. So, I don’t find it surprising that they were considered two of the worst comics of the decade past.

WHAT’S OLD IS NEW AGAIN:

And this heightened awareness of the creator as important to the success of a comic is not necessarily a new idea for DC or Marvel. Though loathe to admit it, I believe they have always harbored the fear that possibly these people who were writing and drawing the stories had something to do with the rise or fall of sales figures. But certainly, it was not something discussed openly, and I would hazard a guess that, if they admitted it at all, this acknowledgement was only held for a very few. And even those few would be considered replaceable if they were to step too far out of line – whether that meant asking for too much money or arguing too vehemently against editorial dictates.

When Jack Kirby left Marvel in 1970, and was summarily courted by Carmine Infantino to join DC, Kirby’s arrival was touted with house ads in DC’s line of books. They realized what a coup it was to wrest Kirby – one of the co-creators and the stylistic guide for Marvel comics – from their main competitor. It was a new day for DC, one that, I am sure they hoped, would herald an injection of excitement and passion into their line of books similar in scope to what occurred when Kirby and Stan Lee, along with Ditko and others, started Marvel in 1961.

Contrary to the corporate mandate, Kirby was actively acknowledged as a creator worthy of respect through the advertisements of DC’s books – even if that respect was a promise unfulfilled.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

Ultimately, I think it’s obvious where one’s loyalty should lie as a comic buyer. Yes, the characters in their flashy uniforms with their cool powers are the ones that, for most of us, got us into comics. But following the character, for no other reason than nostalgia, is not a smart decision. And ultimately, I don’t think it’s a healthy decision for the comic marketplace.

Look at the amazing books we get when artists and writers are allowed to make the stories they want:

Neil Gaiman’s Sandman

Alan Moore’s Marvelman and From Hell and V for Vendetta and Watchmen

Grant Morrison’s Animal Man and Doom Patrol and Invisibles

Greg Rucka’s Queen & County and Whiteout

Jeff Smith’s Bone

JMS’s run on Thor and The Brave and the Bold

Steve Ditko’s Mr. A

Warren Ellis on Planetary and Transmetropolitan

Los Bros Hernandez on Love & Rockets

Carla Speed McNeil on Finder

Art Spiegelman’s Maus

Brian Michael Bendis’s Torso

Eric Shanower’s Age of Bronze

the list goes on . . .

If you’re loyal to the character, then you will be the one still buying the book long after it’s become dreck, and that purchasing choice only reinforces the corporate mindset that it’s the characters that push the sales, not the creators.

Whereas, if you follow a creator, and it’s one who’s work you have enjoyed previously, there is a good chance you will not be disappointed. Certainly, a concept might not be to your liking, but if that concept is presented by a creator you respect, then at least you’ll get your money’s worth as far as artistic value. And then, if you wish, you can let the book go, because you don’t need to avert having a hole in your Green Lantern collection, you just need to worry about finding that next great comic you want to read.

It’s easy. Talent wins out every time for me. If you’re still chained to your corporate loyalties, you’re doing yourself a disservice. Stop collecting and start reading. I think you’ll get more satisfaction from your comics than you ever have before.

Thanks,

chris

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment